YEAH, I KNOW YOU WANT TO START WRITING RIGHT AWAY BUT JUST HOLD YOUR HORSES

One day, the great composer Jerome Kern was eating lunch in the cafeteria of a Hollywood film studio when he was approached by a young musician who asked Kern what he was working on.

Kern replied that he was writing the music for an Italian-themed operetta, also for a show-biz type comedy review, and for an Arabian nights epic.

The young musician was suitably impressed and said, “That’s astonishing….an Italian operetta, a Broadway musical, Arabian Nights….how do you compose so many different things?”

Jerome Kern shrugged and answered: “I just keep writing the same old Jewish music.”

+ + +

That point is well-made for us writers. We are going to write for now in one specific genre but as we learned last time there are five things that underpin almost every genre novel — plot, hero, motivation, much action, colorful background. And no matter what genre we’re working in, those five elements are pretty much the same — as Maestro Kern said, “the same old Jewish music.”

That’s the point of jotting everything down in your notebook — and by now, I hope that notebook’s almost full. Keep going, you’re going to need it. You should have a pretty good idea by now, after so many days of thinking, about what your story’s about, who’s your hero, why’s he doing this, what’s the action, what’s the background, where’s it happening? If you’re not kidding yourself, that’s the stuff you should have been writing in your notebook and hopefully putting onto your word processor at night.

So you’ve got all those notes; what are you going to do with them?

Try this: you’re going to work them into a story and here is one of the most important things you’ll ever learn about writing.

Almost every movie, almost every story, almost every novel, almost every story of any enduring value is structured this way….in four parts.

— Situation

— Complication

— Crisis

— Climax

If you’re not sure you believe me, think of the book and movie “Jaws” as an example.

Right. Situation, complication, crisis, climax.

Burn those four words into your mind; they will help you forever in putting together a story that…well, just simply makes sense. Think of other books you liked, movies you’ve liked, and you’ll see that same structure running through all of them like a bass note underlining a melody. You may not always pay attention to it as a reader, but it’s almost always there, and as a writer, you have to honor it….because it works.

As a matter of fact, in my own writing, I often rely on that structure, not just for a whole book, but often for chapters, and quite frequently for individual scenes. The structure itself puts tension and action and drama into everything it touches — and that’s what you want your book to do. And that’s what your readers will also want your book to do. Readers have a comfort zone and this structure will put them in it.

Memorize it; learn to recognize it; and most important, learn to use it: situation, complication, crisis and climax. Start thinking of the story of your novel in those terms. You’ve jotted down a number of ideas for action in your book. Start squeezing those ideas into that four-part framework. Maybe you’ll struggle at first but then the lightbulb will come on over your head and you’ll see the structure in front of you, and once you see it, you’ll never lose it, and suddenly pieces will start to fall into place.

Think like a novelist. That’s what you are, you know.

+ + +

Along the way, as these blogs continue, we will get deeper into writing techniques and structures and theme and dialogue and a host of other essentials but for now, while you’re still building the story of the novel you’ll soon be writing, today we’ll touch on one of the very critical things you’ll have to master to write your book well. And that super-important thing is:

YOUR CHARACTERS:

(Some of this might sound like overkill and be heavy lifting, so be prepared to read it a couple of times. Eventually, it’ll make sense.)

Everybody’s favorite hero is the person he wants to be. Acne-riddled teens leaving a movie theater, mumbling the name: “Bond. James Bond.” That’s who they want to be. (Curiously, Ian Fleming picked the name James Bond from the author of a book on birds in the Caribbean. Fleming thought it was the dullest name he’d ever heard. Guess again, Ian.)

To produce good characters in your writing, you have to have a clear mental image of them. From that, you give your character a couple of conflicting personality traits. Maybe a character is wealthy and gives millions to charity but never leaves a tip in a restaurant because he thinks tipping is a scam.

You present your character with traits like these — either directly by writing it as author or, even better, by showing it in action, in description, in the character’s speech, and the character’s thought.

You can make a character alive by writing about pain and jeopardy to make him sympathetic to your reader so that your reader cares.

As a boy, I remember a movie where Tarzan is asked by Jane to fight against some Nazis who have come to their neck of the jungle. But Tarzan refuses; the Muhammad Ali of his time, he’s got nothing against those Nazis. But then they kidnap Tarzan’s son, Boy, and Tarzan bestirs himself, sticks a knife in his mouth, and says “Now Tarzan fight.” One of my early movie memories but it’s been with me my whole life and I almost always, in my books, have a “Now Tarzan fight” moment. I recognize it when it’s coming but I can’t escape it. Every character you’ll ever write is you. Some little piece of you; some little corner of your mind that often you’d rather not confront openly; but it’s you. Flaubert wasn’t fooling when he said: “Madame Bovary, c’est moi.” It’s me. They’re all me. And in your books, they’ll all be you.

Once again, you have to see them clearly in your mind to write about them. One way is to cast your friends or acquaintances as characters in your book. Another way is to cast the eventual movie while writing your book. In the writing of a novel called “Jericho Day,” in my mind I cast the young Burt Lancaster as the hero, Luke Darling, because I know the look of the square-jawed stubborness of Lancaster. I could envision the insolent movement of his circus performer’s body. In the book is also a fast talking, wild man, military friend of Darling’s. In my mind’s eye as I was writing, I cast Robert Culp in the role and every time I see that book on my shelf, I see Lancaster and Culp. If I read a line of dialogue, I hear Lancaster and Culp.

Now if everybody did that, wouldn’t everybody have the same characters?

No, for the same reason that you, reading this, might look at J-Lo and like her legs or smile or eyes or…whatever…or look at Brad Pitt and like his smile, his eyes, his physique or his girlfriend. You take from each character what interests you and, perhaps, nobody else in the world. It’s a kind of shorthand that lets you see your characters and know them and thus be able to describe them.

Think of Sherlock Holmes, the most well-known fictional character in all history. Everybody knows what he looks like. But Arthur Conan Doyle gives only a few sentences in all the stories about Holmes’ physical description. We knew, for 60 years, what Holmes looked like because we all saw Basil Rathbone play him in ten thousand different awful movies. Now a new generation will probably have a new vision of Holmes in their minds, based on the actors Jeremy Brett and Robert Downey Jr. — if and when he’s able to work. Or they will picture him as their mind sees him and that’s the best way of all.

If I write a character entering a room, I see him in my mind. Does he enter the room like John Wayne? That’s one way. Burt Reynolds is another way. Dustin Hoffman, as Ratso Rizzo, is still another way.

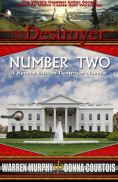

And remember this: a great hero needs and deserves a great recognizable villain. That is what was wrong with a movie called “Remo Williams: the Adventure Begins,” which was based on my Destroyer book series. In the Bond movies, 007 confronts people who want to nuke London or steal all the gold in Fort Knox etc. etc. My guy, Remo Williams went up against some mope who was selling cheap rifles to the government…and no one gave a damn. Great heroes need great villains; otherwise they just look silly.

+ + +

So much to cover; so little time.

It goes without saying that with a good character, a good name is a great help. (Forget Ian Fleming who didn’t know what he had with James Bond.) Dickens had Mr. Bucket, the first slogging detective. He also had Uriah Heap. And Mrs. Haversham. Write down names in your notebook. Read Dickens again; nobody did better names than he did.

Another side-note. Basically I hate research into facts and history and blah and blah. But with characters, you need to know more about them than what you’re going to write, because you need to understand your character and you just won’t ever know when you might want to know something more about him than you’ve already written. Think. Dammit. Think.

So you can’t think of character traits? Here are some opposites for you:

Timid. Adventuresome. (but afraid of wife.)

Achieving. Lazy.

Carefree. Nervous. (Except when doing brain surgery.)

Neat. Sloppy.

Optimist. Pessimist.

Passive. Active.

Quiet. Noisy.

Brave. Cowardly.

Rigid. Flexible.

Sarcastic. Mealy-mouthed.

Suspicious. Trusting.

That’s a start that I borrowed from somebody…(all right, stole.) You can think of dozens more. They will help you create living characters that your readers will empathize with.

+ + +

EXERCISE:

Observe a stranger at a restaurant. Look at him. Really look at him. Most of us never look closely. Good suit? Cheap suit? Shoes worn down? Hair trimmed or shaggy? Invent facts about him. One-liners with data about his past and present life. Plan to make him a character in your book. Make your list of notes and then, without referring to the list, write a character sketch later. You’ve thought him through, so you can do it.

As novelists, we create a character not by what we tell but by what we show. What does that character say? What does he do? What do others say about him? What do they think of him? What would he do if he saw a stranger slapping a kid at the local Walmart’s? That’s characterization and it makes your fictional people come alive.

MINOR CHARACTERS: Not all characters have equal weight. “Lulu” is more important than the driver who is taking her to the hospital, unless the driver is an assassin we introduced earlier who tears the filter off cigarettes before killing and now he stops at a red light and takes a cigarette and tears off the filter…..and…hey, it’s your book, you write it.

There is a hierarchy of character. Minor characters, you let vanish. Usually you bring them alive for a moment by using stereotypes. Literary profiling, if you will. Stereotypes are not necessarily evil or bad; they are characters who are typical members of a group and your readers know the group…cabbie, cop, waitress, mugger, telephone operator, prostitute, lawyer, doctor, politician, drunken Irishman (What? Are there still some of those?), Italian who talks with his hands. We might not like stereotypes of groups to which we belong but as writers they work. These are place-holding characters; they do their job and disappear into the night.

Sometimes though they might do a little more. They won’t be in the real action but they set the mood, they add humor, they make the setting more believable. You can do this by making placeholders eccentric or obsessive. I read analysis once of an old flick called Beverly Hills Cop. It featured a clerk in an art gallery. He was effeminate. By itself, that’s not unusual. But he had an Israeli accent, and that was unusual because foreigners weren’t generally treated as effeminate queens — (although today H’wood can say anything it wants about Christians and Jews. You can tell this was an old movie.) What that character did however in the film was to help make Detroit cop Eddie Murphy, the star, feel even more alien in L.A. than he otherwise would have.

MAJOR CHARACTERS: They can’t usually be wildly eccentric or the reader won’t believe them. Characterization is not a catalog of quirks. Raising orchids. Likes chihuahuas. A Lithuanian dwarf who cracks his knuckles before drinking his coffee. Always wears red shirts. Likes one black shoe and one brown one. Okay, we can recognize him now but is he a character? Short answer: no. What does he do? What does he say? What does he think? Knowing the answers to those questions…now, that’s characterization.

Yes, major characters should be of heroic proportions but none are perfectly good. The strongest Achilles has a weak spot; the smartest has a dumb spot; the most honest cheats on the golf course; that is what makes people real.

Side events count too. Sometimes you imply things. Imagine a man whose checks the desk clerk accepts at a $10 per hour motel. That tells you something about him, doesn’t it? He’s not a stranger there, for one thing. For another, he’s probably not married because he doesn’t care who sees his cancelled checks. And of course the reader’s got to understand the significance of what you just showed him.

You don’t always examine characters under a microscope. You can do it through other’s eyes. “Stand up, girl. Your father is walking by.” That’s from “To Kill a Mockingbird” and we certainly learn a lot about Atticus Finch from just that line, don’t we?

The late Robert Parker’s Spenser character was interesting. He was a yuppie. He ran, he lifted weights, he liked to cook, he liked unimposing little wines with sardonic personalities, he pretended he didn’t care about clothes but somehow always managed to wear the same basic uniform;, he lived with a woman, Susan the insufferable, who could psycho-babble Jay-Z into impotence. But the characterization hook was that Spenser spent his life being a private eye and shooting people, which was totally alien to the character’s nature. That started to round him out and make him real. Without that hard edge, he’d have been just another fan of Barry Manilow.

What Parker did with Spenser is called working against the stereotype. Consider a cop who practices yogic meditation and has a child bride. He is not a Republican bowling team beer drinker. If you work at it, he has a chance, in your hands, of becoming a living character.

Just in passing, most writers have blind spots. Some writers can’t do cops. Some can’t do the opposite sex. Some can’t do a different race from theirs. That problem usually comes because we start with the label, rather than the person. Start with the person. If you do that, you can write anybody.

+ + +

Think about your major character. Tell him, I know your secret. Every character has one.