THAT FAMOUS NOVELIST YOGI BERRA SAYS WE’RE NOT THERE YET BUT WE’RE GETTING CLOSE:

Okay, ladies and gentlemen, here’s where we are now — at least if you haven’t succumbed to being a phony and haven’t already started working on your Nobel Prize speech.

If you’ve been working at it, you’ve come up with an idea for a novel. You’ve learned what five things go into a genre novel and re-read a novel that you liked in that genre.

You bought notebooks and made notes about characters and action and plot and motivation and interesting people and names. In short you’ve been collecting all the ingredients for a great pot of stew.

Our second segment gave the four ground rules for telling a story — the rules that never seem to change. Situation. Complication. Crisis. Climax. And then we discussed a lot about creating characters that are alive because without characters that a reader cares about, there is simply no book.

And you also went ahead and made a brief general outline of the novel you really liked, to be able to analyze it more closely. That’s good, because we’re soon going to be doing the same thing.

+ + +

Just a note of snivelling and complaining from me. One of the problems with teaching like this is that — believe it or not — I know this stuff. And I have to presume that you don’t. But I want you to get started writing soon, so what I’ve tried to do is hit the high points first, the things that are most important, and later, as you’re writing, I’ll fill in some of the stuff I haven’t yet been able to get to. And, there’s a helluva lot of it.

At any rate, by now, you should have some pretty good idea of what your story is about; who are your main characters, what is your conflict. What situation, complication, crisis and climax. (I keep repeating that because there’s nothing more important.) You’ve been working for weeks now; you’ve got this much done.

Now what I’m about to assign is going to sound either simple or impossible. Take your pick, but it is neither. It is just a tough thing that you have to learn to do so you don’t spend all your time spinning your wheels. In the words of that great writer, Yogi Berra, “If you don’t know where you’re going, how do you know when you get there?”

Stick with me and we’ll get you there. And this is how you start.

+ + +

Write a one-sentence outline of the story of your novel-in-progress.

One sentence.

Tell all your story in one sentence. And don’t give me a lot of bulldookey. One sentence.

When I gave this assignment for the first time to a college class I was teaching, first of all they started to write descriptions: “a blistering expose of the Republican party and how it hates me.” Or “an inside look at some of the candidates from the point of view of Sarah Palin’s gynecologist.”

“No, morons,” I explained patiently. “I want a sentence that tells the story of your novel.”

One of the smartass students said it was possible that I might be able to outline one of my cheesy books in one sentence but his magnum opus? He certainly doubted it.

I asked said student if he knew what a comma was and its use in a sentence. When he said he did, I suggested this to him:

“Ahab, the obsessed, revenge-seeking captain of a whaling ship, sails his vessel and its crew to destruction, in a final confrontation with the great white whale that had crippled him years earlier.”

That is, I suggested further to this smarmy little snot, a one-sentence outline of a book by Herman Melville, titled Moby Dick.

“It is the greatest novel ever written by an American author. If Melville’s masterpiece can be encapsulated in one sentence, perhaps if you try hard, you might be able to do the same with your work of exalted genius.”

+ + +

So that’s your assignment and that’s what you’ve got to do. And, as I said, by one sentence I don’t mean some generic pap about how “people on the north side of Detroit face a life of poverty bravely and honestly.” That’s generic junk and it is unacceptable here.

So you might ask, why one sentence? Fair enough. Because until you can write one sentence, you don’t know what your book is about. If you don’t know what it’s about, you can’t write it. Period. Case closed. I can’t help you. God can’t help you. Nobody can help you. You are helpless and hopeless.

If someone were to ask you, “That movie you just saw. What’s it about?” You could tell him in a sentence. Well, imagine your novel-to-be is a movie already and tell us about it in a sentence. Just make the sentence a little bit bigger, a little bit better, a little bit smarter and you’ve done what you had to do. What you’re doing, you see, is making choices. What is the most important element of this novel’s story?

But you’re going to be surprised at how hard it will be. It’s supposed to be because here is where we separate the grownups from the intellectual children, separate the writers from the someday-i’m-gonna’s.

There’s a story about a Hollywood screenwriter who had a contract for a war-cum-adventure movie about Vietnam and who decided that since he had time he was instead going to write “a searing indictment of American policy in the far East.” (Liberals are always writing searing indictments.) Great idea, he told himself, then put some powder in his nose and went and sat by the pool. Several months later, the producer called and asked “Where’s my screenplay?” The writer, who hadn’t written a word, said, “I’m taking it in a different direction. It’s going to be a hilarious dark comedy about soldiers in a far-off land.” Then he put more powder up his nose and sat by the pool again, writing nothing. A month later, the producer called and said, “Where’s my screenplay?”

The writer responded, “I’m thinking it might be best as science fiction. An epic, you know.”

The producer said, “Here’s what I’m epically thinking. If I don’t have my screenplay in two weeks — the war adventure movie we outlined so long ago — I’m going to send people to your house to break your legs.”

So the writer wrote the wartime shoot-em-up he’d been hired to write and did it in two weeks. Later, he bragged that he had been working on this movie “for two years.”

A lesson there. It’s hard to write if you can’t make up your mind what you’re going to write about. Yes, you’re going to have to spend time, a lot of time perhaps, on creating this one sentence. But every minute you spend “upfront” before you start writing, may save you hours, days, months later on. And may also guarantee that nobody breaks your legs.

+ + +

After almost two hundred books, I still do this. I sit at the keyboard, trying to craft the sentence that tells the story of the book I want to write. I write one sentence and it doesn’t work, and I write another and another, and I keep thinking about it and keep going, getting closer and closer, and then one day, I have worried this bone so much that it is finally clean and there is my sentence and there is my story. The hardest part of the book is now done. Believe it or not, that one sentence is the hardest part — getting it right at the beginning.

Earlier I talked about a book by the brilliant Molly Cochran and me called “The Temple Dogs.” Here is a one sentence outline of that book which is damned near as complicated as “The Godfather” and “War and Peace” combined.

“When his sister is murdered at her wedding reception by a pair of New York City mafia goons, Japanese-American yuppie Miles Haverford goes to Japan and brings back to America a group of Yakuza crime family assassins who extract revenge for the young girl’s death.”

Now that’s one sentence. It’s a long sentence, to be sure, but it’s one sentence and it’s what the book is about. I mentioned earlier that the book is also about people who live up to some code of honor against a gang of thugs who have no code of honor. The book is also about Miles Haverford coming to understand just who he is, what is his role in this Japanese crime family; it is a story of forbidden love between Miles and a Japanese woman; and it is an astonishingly deep look into the Japanese criminal underworld, with a Godfather who could make Don Corleone blink…along with a new Godfather who will stun you.

It is all those things. But the big story, the thing that drives the book, is the single sentence up above. Write your one sentence. And be sure to put the name of your lead character in it; that will discourage you from writing bland filler material and will force you to be specific about the novel you are getting ready to write.

+ + +

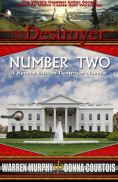

Another example. My Destroyer series has 150 books but a single sentence that covered the entire scope of the series would go something like this: “After his fake execution for a murder he didn’t commit, ex-cop Remo Williams is forced to work for America’s secret crime-fighting agency CURE, while being trained by the world’s greatest assassin, the aged, ageless, cranky, mercenary, mystical Chiun, Master of Sinanju.”

That’s possibly as accurate a sentence as anyone could write about an entire series…especially one that grew from Dick Sapir’s and my first idea which was to write about a crime fighting Jewish psychoanalyst in New York. Named Bernie. (Oh, well, there’s always tomorrow.)

Anyway, as I said, writing one sentence forces you to think what is the story, what is it really about, and not the flapdoodle that embroiders it and covers it in disgusting French gravy. It’s the meat that’s underneath that makes the meal.

If you can’t write that one sentence, it’s because you don’t know what your proposed book is really about, and if you don’t know what it’s about, it’s not a story at all, it’s a shopping list. Writing isn’t about typing; writing is about thinking. If you’re too lazy to think and to work, please consider needlepoint as a hobby. This ain’t for you and I don’t have time to waste.

It’s interesting to note that in Hollywood where they are always looking for blockbusters — but then don’t know what to do with them so they go back to filming comic books — the thing they most desire is “high concept.” That means a clean plot, a story you can tell in one sentence. Think “Gone with the Wind,” think “Jaws,” think “The Exorcist.” These could each be described in one sentence, but it would be a little more generalized than the sentence you want to write about your book. High concept, as practiced in Hollywood, is a selling document; yours is a writing document.

OKAY, YOU’VE HAD ENOUGH? SORRY, NOT QUITE:

If you’ve written your sentence, you’ve done the toughest part, but there’s still more to do.

(I know, I know. You hate me. “When do I start writing, dammit?” Actually, feel free to start as long as you’re sure you’re ready to write and to produce something that doesn’t stink and embarrass either me or you.)

But by my schedule, here’s the next step in the project. Muy importante.

Expand your one sentence into one paragraph. Again, this requires thought, not just finger movements, and I can best illustrate it by showing you how it would work for me. Once again, we go to the book, “The Temple Dogs.”

Here was our first sentence:

“When his sister is murdered at her wedding reception by a pair of New York City mafia goons, Japanese-American yuppie Miles Haverford goes to Japan and brings back to America a group of Yakuza crime family assassins who extract revenge for the young girl’s death.”

Here’s what we add to make a paragraph:

“While in Japan, Miles meets the Yakuza chieftain, the aging Nagoya, and learns that, by blood, he is truly a member of this crime family. But Nagoya’s assistant and heir, the street warrior Sato, also of mixed blood, tries to drive Miles away because the young American and Sato’s woman, Lady Tomiko, are clearly falling in love. Yet Miles eventually wins over the Yakuza men and Sato is among the group that returns with Miles to New York to slowly, individually, bloodily tear apart the DeSanto Mafia crime family.”

Do you see what goes on there? In fleshing that first sentence out into a long, full paragraph, we have added additional characters, sub-plots, some of the history necessary for the book to be full and to work. And in doing so, once again, we had to choose. In writing that paragraph, we left out dozens of people who appear in the book, all the other Yakuza fighters who make the New York City trip….what we did was decide what were the most important elements and include only them. By making the choices now, we determine what are the parts of the book essential to the telling of the story. It’s your book; you have to make those decisions…but frankly, after writing your first sentence, this solo paragraph is easier.

TAKE A DEEP BREATH: ALMOST DONE HERE

BUT JUST A LITTLE MORE HEAVY LIFTING.

We’re getting close to the end now. You have a big fat paragraph. The next step is to add to it some or most of the other important elements in another paragraph or two, and when you do that, your story is basically complete in your mind — at least as far as it has to be for now.

Rather than lecture, it’s probably easier to illustrate what to do. So here, once again, is “The Temple Dogs” expanded paragraph from up above:

When his sister is murdered at her wedding reception by a pair of New York City mafia goons, Japanese-American yuppie Miles Haverford goes to Japan and brings back to America a group of Yakuza crime family assassins who extract revenge for the young girl’s death. While in Japan, Miles meets the Yakuza chieftain, the aging Nagoya, and learns that, by blood, he is truly a member of this crime family. But Nagoya’s assistant and heir, the street warrior Sato, also of mixed blood, tries to drive Miles away because the young American and Sato’s woman, Lady Tomiko, are clearly falling in love. Yet Miles eventually wins over the Yakuza men and Sato is among the group that returns with Miles to New York to slowly, individually, bloodily tear apart the Mafia crime family.

Okay and now to finish this up. (And I hate to do this because I’m going to wind up telling you the whole story and then nobody’s going to buy this book which is just being reissued. Damn. Being honorable always carries too high a price tag.) Aaah, phooey. Anyway, here’s how this brief summary will finish the story beneath “The Temple Dogs.”

“In New York, the DeSanto crime family is dead or in jail. Miles’ parents in New York are safe from Mafia reprisal. The Yakuza assassins are ready to return to Japan, but Miles has decided that the life of a buttered-bun Wall Street lawyer is no longer for him. He bids his family goodbye and returns to the Japanese home of Yakuza chieftain Nagoya. It is time for Nagoya to pass on the leadership of the criminal clan and his choice is his faithful assistant, Sato. But Sato declines the ceremonial cup and instead stands beside Miles and calls him ‘Someone whom the gods have sent from across the sea to lead you to tomorrow.’ And then he bows to Miles, the new leader.

“In the book’s final scene, Lady Tomiko and Miles make their way up the four hundred steps of the shrine of Kumanomichi to take their wedding vows.”

And that’s the story of a book. I want your story to be that thorough and I want your book to be that good.

Comb your hair.